Bukhara’s Healing Recipe

In the heart of the ancient Silk Road, a legendary city is offering a radical prescription for our fractured times: a feast of art, community, and memory designed to heal.

The dust of Bukhara is the color of time itself—a warm, sun-baked ocher that clings to the mud-brick walls of madrasas and the curved domes of 16th-century trading halls. To walk its labyrinthine lanes is to feel the weight of a millennium, to breathe air thick with the ghosts of merchants, mystics, and scholars. For centuries, this was a city of transaction. This autumn, it has become a city of transformation.

The inaugural Bukhara Biennial feels less like an art exhibition and more like a collective spiritual pilgrimage. Its theme is not a detached academic thesis but a universal human need: “Recipes for Broken Hearts.”

The idea, both simple and revolutionary, flows from a legend as savory as the city’s national dish, plov. As the story goes, the 10th-century polymath Ibn Sina—the father of modern medicine, who called Bukhara home—invented the fragrant rice pilaf to cure a prince dying of a broken heart.

"Recipes are incredible because they allow us to time travel. I really miss my grandmother, but if I cook one of her recipes, I can feel like she’s with me."

– Diana Campbell (Artistic Director of Bukhara Biennial’s first edition, “Recipes for Broken Hearts”)

A Personal Recipe

For the biennial’s two guiding forces, the theme is deeply personal. “The title came very quickly,” explained Diana Campbell at the opening-day panel. For her, recipes are conduits of memory and presence.

This sentiment—though forged in the crucible of history—is echoed by Gayane Umerova, the biennial’s commissioner and Chairperson of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF) and of the National Commission of Uzbekistan for UNESCO Affairs. The idea for a biennial in Bukhara, she revealed, began four years ago as a way to “bring some life to these buildings.” But its soul is rooted in stories of survival and connection.

“My grandmother from my father’s side came from Moscow,” Umerova shared, her voice softening.

“Because of the war, she had to be sent here with her family. She was living in a neighborhood with Uzbek and Samarkand Jewish families, and in those difficult times, my grandmother would just cook with her neighbors. That’s how she learned all the Uzbek and Jewish recipes. So in our house, our New Year’s dish is a completely Jewish dish. This is how she learned about the culture, despite the hardship. This is how she came to belong.”

This is the biennial’s foundational truth: recipes are not just about food but about identity, resilience, and the bonds we forge in times of rupture.

A Prescription Written in the City

Forget the sterile white cube. The biennial’s genius is its seamless integration with the city itself. The entire experience is a prescribed journey that follows the path of the ancient Shakhrud Canal, weaving through the living tissue of the mahallas (neighborhoods). Over 70 projects are embedded in public spaces, inviting a gentle collision between contemporary art and daily life.

For travelers, this offers a profoundly different experience. It moves beyond the passive consumption of history often associated with large tour groups. Instead of seeing Bukhara as a beautiful museum piece, you are invited into a living conversation—a chance to witness the city not just as it was, but as it is becoming.

This immersive approach is fundamental, for what makes the Bukhara Biennial truly unique is that none of its art was shipped in a crate. Every piece is a new commission, born of Bukhara itself. Artists were invited not just to exhibit but to reside, research, and create in collaboration with the local community. “We create art here, with the local people, with local artisans, for the city,” emphasized Gayane Umerova.

This ethos deliberately dissolves the tired hierarchies of the art world. “I’ve always been interested in blurring this line between who we call an artist and who we call an artisan,” explained curator Diana Campbell.

“We shouldn’t create this gap. It should be linear, and they should be respected the same way,” emphasized Gayane Umerova. Here, master craftspeople, whose families have perfected their skills for generations, are reframed not as assistants but as co-creators on an international stage.

The formal journey begins at the Caravanserai, a complex of four 18th-century merchants’ inns, some restored and some left in poetic ruin. This is where you are invited to face the break. The crumbling walls feel like old wounds, the small, cell-like hujrasevoking the isolation of grief. The art here is global, from Brazil to Bangladesh, a silent chorus reminding you that heartbreak is a universal language. It’s a space that proposes we need not overcome heartbreak but learn to move forward with it.

From this raw honesty, you are offered sanctuary. You step into the Gavkushon Madrasa, a 16th-century school masterfully transformed into the “House of Softness.” “It’s a space where, when the world is hard outside, we can soften our hearts and learn from our feelings,” Diana Campbell explained. Here, visitors gather under a delicate, floating canopy that filters the brilliant sun into a gentle, shifting mosaic. This is “Patterns of Protection,” the work of Indian-American architect and artist Suchi Reddy.

“The inspiration came from ikat,” Reddy says, standing under her creation. “I grew up thinking it was a South Indian tradition, and I was surprised to realize it came from Uzbekistan. In collaboration with a local artisan, we isolated a pattern that symbolizes protection.” The result is a grand, woven canopy. “As the sunlight moves, the shadows of these patterns are projected,” she described, “creating beautiful patterns of comfort.”

A Vision for the Future

What truly sets this biennial apart is its long-term vision. It is not a fleeting festival but phase one of a sustainable cultural ecosystem. “We are here to stay,” Umerova declared, her gaze firm. “We are going to make this biennial flourish every time.”

The project is a cornerstone of Uzbekistan’s national strategy to build a robust creative economy, providing jobs for its remarkably young population (over 60% are under 30). “We need to invest in our youth,” Gayane Umerova explained, “to build the next generation of the middle class, which is really important for our nation to grow.”

The most charming proof of this commitment is tucked away in a restored 19th-century mosque: a Pop-Up Children’s Library. Created in partnership with the Nationwide Children's Library, it is a jewel box of a space where the next generation can discover the world. “When kids come to our library to get a book about English,” Umerova said, “at the same time they see a book about architecture or artists. You get their attention from an early age.” It is a quiet, profound investment in the future, planting the seeds of creativity.

The Taste of Healing

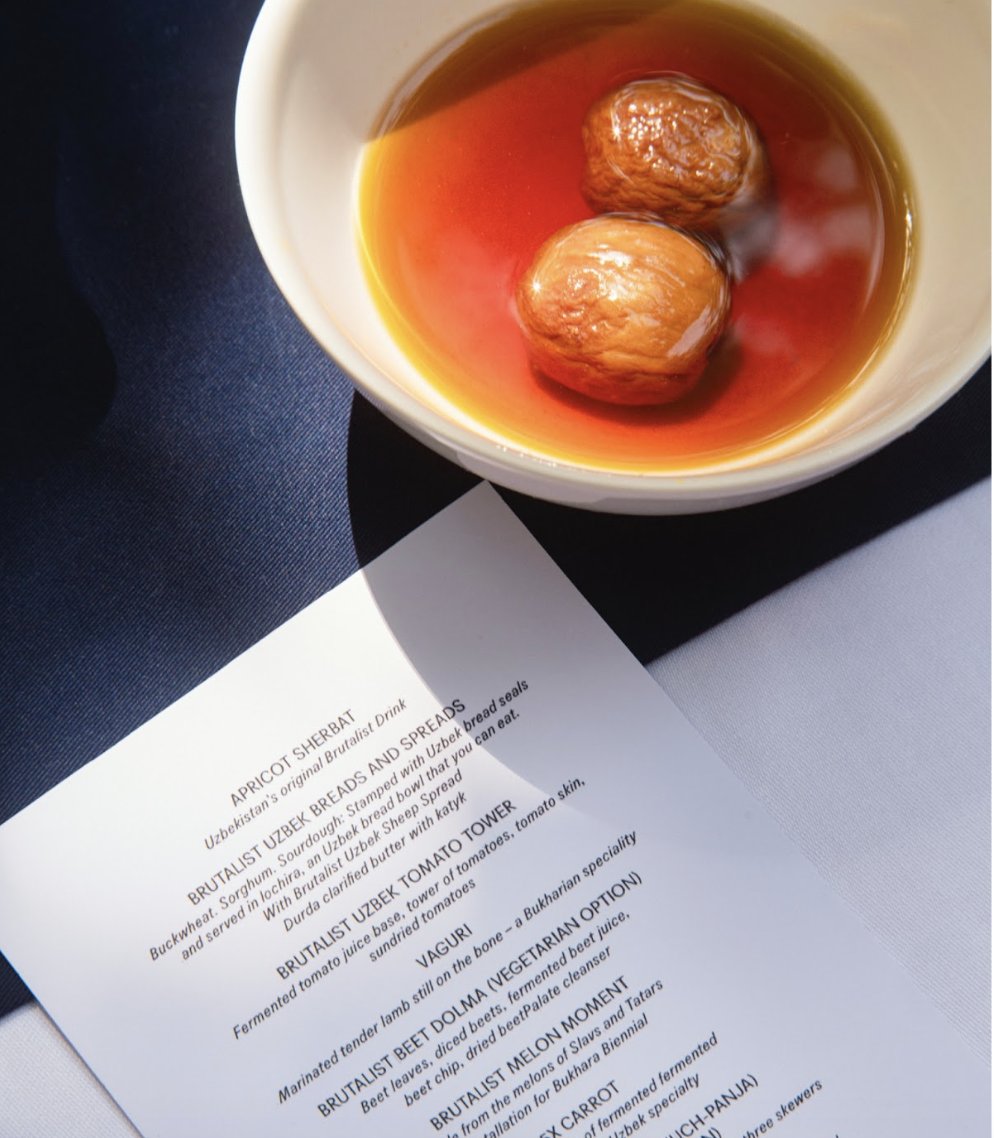

What’s a recipe without food? At Café Oshqozon—whose name means both “stomach” and “a vessel for cooking”—the theme becomes deliciously tangible. Unlike a typical museum cafe, this is a culinary installation where chefs create dishes inspired by Ibn Sina. You’re not just eating; you’re tasting a story of spices that traveled the Silk Road. In that simple, profound act of sharing a meal, you understand the biennial’s core message.

The result is a rare and powerful suggestion: that a walk through a timeless city, a conversation with an artist, a moment of awe, and a meal shared with new friends is not just a holiday but a form of therapy. It is a prescription for joy. As I left Bukhara, the ocher dust on my boots, I knew the answer to the city’s question.

Can a place heal a broken heart?

This one has the recipe.

** GETTING THERE **

The journey is part of the experience. You can fly directly into Bukhara International Airport (BHK) from hubs like Istanbul, Dubai, and Moscow. A taxi to the Old City takes about 15 minutes.

Alternatively, flying into the capital, Tashkent (TAS), allows for the remarkable four-hour journey on the Afrosiyob high-speed train. It’s a comfortable, modern passage through a timeless landscape that serves as a perfect mental transition. Book tickets in advance online at railway.uz.

** ON THE GROUND **

Dates: September 5 — November 23, 2025

Hours: Tuesday — Sunday. 10 AM — 10 PM in September | 10 AM — 8 PM in October and November.

Admission: Free